Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Nigeria, is supposed to be a symbol of order, national identity, and administrative efficiency. Instead, it has become a city in quiet paralysis—a capital that looks functional from a distance but is hollow at its core. Government offices sit locked; public primary schools are empty; hospitals operate skeletal services, and civil servants loiter on protest grounds rather than at their desks. Meanwhile, parents, patients, traders, and transport workers bear the hidden costs of a system that has repeatedly failed them.

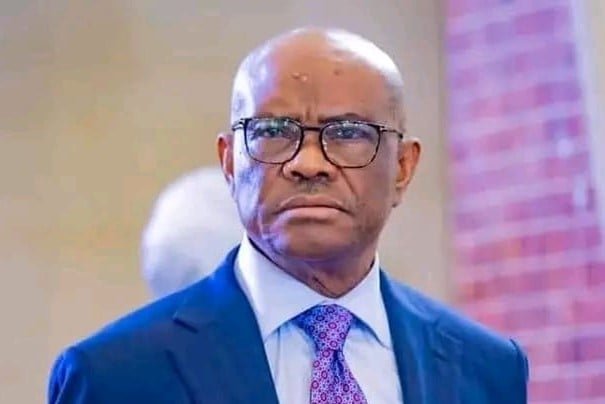

At the center of this standoff is Nyesom Wike, the combative former governor of Rivers State and current Minister of the Federal Capital Territory. Appointed with high expectations and endowed with sweeping authority over the nation’s capital, Wike projected an image of no-nonsense governance and decisive leadership. Yet as labour unrest, contractor protests, and civic discontent have escalated, critics argue the minister has adopted a posture of studied indifference—what many describe as “playing the ostrich” while Abuja grinds to a halt.

This is more than a story of strikes and protests. It is a tale of structural dysfunction, blurred accountability, political distraction, and the human cost of governance failure in a city meant to exemplify Nigeria at its best.

A Capital in Crisis

The current wave of unrest did not erupt overnight. It is the culmination of years of unresolved labour disputes, unpaid entitlements, and institutional buck-passing among the Federal Capital Territory Administration (FCTA), the six area councils, and the federal government. Teachers, health workers, and other categories of FCT employees have repeatedly accused authorities of reneging on agreements, delaying salaries, and ignoring negotiated welfare packages.

Each strike follows a familiar pattern: unions issue ultimatums; protests erupt; government promises engagement; and services remain suspended until partial concessions are made—often months later. But what distinguishes the latest crisis is its scale and simultaneity. Never in recent memory have so many sectors of the FCT been disrupted at the same time.

Public education has suffered prolonged shutdowns. Healthcare delivery has weakened. Core administrative functions have stalled. And the result is a capital city that appears functional on the surface but hollow at its core.

On Monday, the FCT descended into near paralysis. Workers across ministries, departments, and agencies of the FCTA withdrew their services indefinitely following the expiration of a seven-day ultimatum issued by the Joint Union Action Congress (JUAC).

In a statement signed by JUAC President Comrade Rifkatu Iortyer and Secretary Comrade Abdullahi Saleh, the unions accused the FCTA of ignoring repeated engagements and failing to address long-standing welfare and labour issues, including unpaid promotion arrears, delayed promotions, non-remittance of pension and National Housing Fund deductions, and what they described as the “illegal extension of service” of retired directors and permanent secretaries.

The ultimatum, which took effect from January 7, 2026, was formally communicated to top FCTA officials, including the Minister of State for the FCT, the Chief of Staff, the Head of Service, and security authorities—yet nothing tangible happened.

Union leaders also described the 2024 promotion examinations as a “colossal failure” that left many workers unfairly stagnated. “The system has failed us repeatedly, and we cannot continue to work under this uncertainty and injustice,” Comrade Saleh said during a protest at the Unity Fountain in central Abuja.

Contractors Threaten Economic Shutdown

As civil servants downed tools, indigenous contractors simultaneously took to the streets, barricading the Ministry of Finance over an alleged ₦4 trillion debt owed by the Federal Government for completed 2024 capital projects.

The All Indigenous Contractors Association of Nigeria (AICAN) said only about 40 percent of the debt was paid following protests in December 2025, leaving thousands of contractors trapped in crippling bank loans. AICAN President Jackson Nwosu warned that the group was prepared to shut down the nation’s economy if the outstanding balance was not cleared.

“We borrowed from banks to execute government projects,” Nwosu said. “Many contractors have lost their properties, some have died. If they don’t kill us, the economy of this country will die.”

AICAN Vice President Ode Agada appealed to the international community to intervene, describing the situation as “inhumane” and economically destructive. Contractors also sent direct appeals to Minister Wike to settle debts in the FCT, warning that banks were threatening arrests over unpaid loans.

The frustration among contractors is compounded by repeated promises from federal authorities that remain unfulfilled. Industry analysts warn that a continued delay in clearing these debts could trigger a broader economic disruption beyond the FCT, threatening the viability of the construction sector nationwide.

Teachers’ Strike Keeps Children Out of School

The Nigeria Union of Teachers (NUT), FCT chapter, had last year accused area councils and the FCT administration of failing to fully implement the national minimum wage and related allowances, despite repeated agreements.

NUT Chairperson Abdullahi Muhammad said public primary school teachers were being discriminated against, while their secondary school counterparts enjoyed full wage benefits. “We are not working for charity. The wage can no longer sustain teachers living in the FCT,” Muhammad said. Teachers are demanding full implementation of the ₦70,000 minimum wage, payment of arrears, allowances, and overdue promotions.

Adding to the controversy, NUT alleges that ₦4.1 billion released to area councils to address the crisis was diverted—an accusation officials declined to comment on directly. The result is that thousands of children in the FCT have been kept out of classrooms for months, raising concerns about learning loss, literacy decline, and the widening education gap between private and public school pupils.

Doctors Also on Indefinite Strike

Healthcare in the FCT is similarly in jeopardy. Resident doctors in public hospitals had vowed to continue their indefinite strike over unpaid salaries, delayed allowances, and poor working conditions.

The Association of Resident Doctors, FCTA chapter, last year also accused the administration of failing to implement agreements reached after interventions by Minister Wike and the National Assembly. Doctors say some colleagues have not been paid for months, while others are underpaid compared to peers in federal institutions.

“The situation is untenable. We are treating patients with bare minimum resources while our families go hungry,” one striking doctor said under condition of anonymity. Hospitals across Abuja are running skeletal services, and patients requiring routine and emergency care are facing long delays or are turned away entirely.

Read also:

- Wike: I won’t leave PDP, vows to fight from within

- Wike replies Ayu: Be humble and relinquish chairmanship position

- Birabi accuses Wike, Amaechi of splitting, enslaving Ogonis

Mounting Anger, Silence from Wike

Despite the scale of disruption—closed offices, stalled projects, empty classrooms, and strained hospitals—Minister Wike has faced criticism for offering rhetoric without tangible action. Union leaders say repeated threats by the minister to sanction erring area councils or withhold allocations have not translated into results.

Wike, known for his fiery persona and political acumen, has often been decisive in his previous governorship. Yet in the FCT, civil servants and contractors describe his response as inadequate, creating the impression of political distraction or selective inaction.

Labour leaders warn that if the administration continues to ignore their demands, Abuja is sitting on a social and economic time bomb that could explode at any moment.

Political Implications

Analysts warn that the crisis could have wider political consequences. The FCT is Nigeria’s administrative and political nerve center. Prolonged disruption undermines public confidence not only in the territorial administration but also in the federal government itself.

“This is a test of leadership for Minister Wike and the Presidency,” said a political analyst. “How the government responds—or fails to respond—could influence perceptions ahead of elections and affect governance credibility across the country.”

For now, the people of Abuja are paying the price for unresolved disputes, institutional inertia, and what appears to be a lack of decisive leadership. The city’s paralysis is more than inconvenience—it is a reflection of governance that has lost touch with its citizens.

Abuja is a city that symbolises Nigeria’s aspirations, yet its reality tells a different story. Workers, contractors, teachers, and doctors continue to fight for what many believe are their basic rights, while a minister with considerable authority remains criticised for inaction.

The crisis in the FCT is not merely administrative—it is profoundly human. It is about children missing school, patients being turned away, families struggling, and livelihoods being disrupted. And until the FCT administration acts decisively, Abuja’s image as a model capital remains aspirational at best, a cautionary tale at worst.

Nigeria’s capital may look like a functioning city from afar, but at its core, it is a city under siege—its paralysis a stark warning of the cost of political indifference and administrative neglect.