For years in Kano, the annual observance of Ramadan has come with an increasingly controversial practice: public arrests of individuals caught eating or drinking during fasting hours by operatives of the Kano State Hisbah Board.

While Hisbah officials argue that the enforcement is rooted in safeguarding public morality and upholding Islamic values in a predominantly Muslim state, critics say the arrests represent a troubling overreach—one that infringes on personal freedoms and blurs the line between religious devotion and coercion.

According to The Trumpet findings, several residents, on condition of anonymity, described scenes of young men being rounded up at roadside food stalls, commercial drivers questioned for sipping water, and restaurant operators warned or detained for serving customers during fasting hours.

“For many of us, fasting is a personal act of worship,” said a civil servant in the city. “It is a sacrifice between a believer and God. When you begin to arrest people for not fasting, it changes the meaning of the worship itself.”

Islamic scholars are themselves divided. While many agree that fasting during Ramadan is obligatory for adult Muslims, they also point out that Islam recognizes exemptions—such as for the sick, pregnant women, travelers, the elderly, and those with valid health conditions. Public humiliation or arrest, some argue, risks contradicting the Qur’anic principle that “there is no compulsion in religion.”

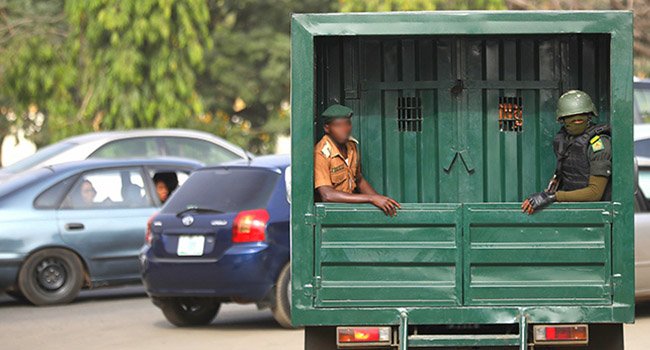

The Kano State Hisbah Board, a state-backed Islamic moral enforcement body operating in Kano State, has historically defended its actions as part of its mandate to promote moral discipline and public decency.

Officials have maintained that open eating during Ramadan in a Muslim-majority society is provocative and disrespectful to those observing the fast.

However, rights advocates argue that such enforcement disproportionately targets the poor—particularly street vendors, commercial motorcyclists, and laborers—while wealthier residents are rarely subjected to similar scrutiny.

In recent years, social media has amplified public frustration, with videos and testimonies circulating online showing alleged arrests and confrontations. Critics describe the trend as “religious policing” that risks alienating youths and non-Muslim minorities living in the state.

Legal analysts also question the constitutional footing of such arrests. Nigeria’s constitution guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

Some lawyers argue that compelling outward conformity to religious practices—even in a Sharia-compliant state—could conflict with these protections.

“There’s a difference between encouraging moral behaviour and enforcing personal piety,” said a Kano-based legal practitioner. “The moment fasting becomes something you’re arrested for not performing, it stops being voluntary worship.”

Beyond the legal and moral arguments lies a broader societal question: What is the role of the state—or quasi-state religious bodies—in regulating personal religious observance?

For many in Kano, Ramadan remains a deeply spiritual period marked by charity, prayer, and community solidarity.

But the recurring controversy surrounding Hisbah’s enforcement tactics threatens to overshadow the essence of the holy month.

As another Ramadan approaches, residents and observers alike are watching closely. Will enforcement continue as in previous years, or will mounting criticism prompt a rethink?

For now, the debate in Kano reflects a larger tension playing out across parts of northern Nigeria: the delicate balance between faith, freedom, and the limits of religious authority in a modern constitutional democracy.