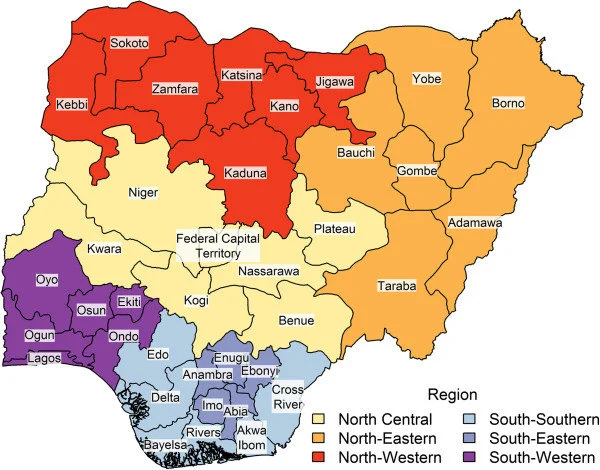

By February 1976, Nigeria stood at a historical crossroads. Fresh from civil war, under military rule, and desperate to stabilize a fragile federation, General Murtala Mohammed announced the creation of seven new states. The objective was clear and ambitious: deepen federalism, bring governance closer to the people, reduce regional domination, and accelerate development across the country.

The states were Bauchi, Benue, Borno, Imo, Niger, Ogun and Ondo. (Oyo, also created in 1976, is impossible to exclude from any honest assessment and is therefore examined here.)

Fifty years later, the verdict is sobering. State creation succeeded politically. Developmentally, it largely failed. What was meant to unlock growth has, in many cases, entrenched dependency, widened poverty, and exposed a persistent truth Nigeria has refused to confront: administrative units do not create prosperity; leadership, planning, and accountability do.

BAUCHI STATE: POTENTIAL WITHOUT STRUCTURE

Created in 1976 and located in Nigeria’s North-East, Bauchi State today has an estimated population of about eight million people. More than half of them live in multidimensional poverty. Internally Generated Revenue (IGR) struggles to cross ₦25 billion annually, leaving the state heavily dependent on monthly FAAC allocations.

Historically, Bauchi should have been an agricultural and tourism powerhouse. The state is endowed with fertile land, livestock, solid minerals, and one of Nigeria’s most iconic tourist attractions — Yankari Game Reserve. Yet these advantages never translated into an industrial base.

Manufacturing remains marginal. Agro-processing is almost non-existent. Tourism infrastructure is weak, poorly marketed, and undercapitalized. Fifty years after creation, Bauchi has no major industrial hub, no strong export-oriented sector, and no functional value chain linking agriculture to industry.

The capital city itself reflects this stagnation: limited urban planning, inadequate infrastructure, and few employment opportunities for a rapidly growing youth population.

Bauchi’s problem is not lack of resources. It is the absence of deliberate economic architecture. Development did not fail here by accident; it was neglected.

BENUE STATE: THE FOOD BASKET THAT NEVER FED ITSELF

Benue State’s nickname — Food Basket of the Nation — has become one of the most tragic ironies in Nigeria’s political economy. Created in 1976 and located in the North-Central zone, Benue records poverty rates between 50 and 55 percent. Its IGR hovers around ₦20–25 billion annually, among the lowest for a state with such agricultural output.

Benue produces yam, rice, soybeans, cassava, maize, citrus, and livestock in massive quantities. Yet almost all of it leaves the state unprocessed. There are no large-scale agro-processing clusters, no cold-chain infrastructure, no food industrial parks, and no export-processing zones.

The result is predictable: farmers remain poor, youth migrate, salaries go unpaid, and the state imports finished food products at higher prices. Benue feeds others but starves economically.

After 50 years, the state has failed to convert agriculture into wealth. This is not a failure of land or labor; it is a failure of vision. A food basket without industry is not an economy — it is a subsidy to others.

BORNO STATE: WHEN INSECURITY ERASES HISTORY

Borno State, created in 1976 in the North-East, tells the most tragic story of all. With poverty levels above 70 percent and IGR under ₦15 billion, the state’s economy has been shattered by over a decade of Boko Haram insurgency.

Historically, Borno was a major Sahelian trade hub, linking Nigeria to Chad, Niger, and Cameroon. Maiduguri was once a vibrant commercial center with cross-border trade, livestock markets, and small-scale manufacturing. That history has been violently erased.

Infrastructure lies in ruins. Schools, hospitals, and markets were destroyed. Millions were displaced. The private sector fled. Humanitarian aid replaced private investment. Dependency replaced productivity. Security failure reversed decades of development in less than ten years.

This tragedy cannot be divorced from political leadership. Insecurity thrives where governance fails. Power without responsibility produces collapse. Borno’s story is not just about terror; it is about the long-term consequences of leaders who prioritized control over progress.

IMO STATE: HUMAN CAPITAL, WASTED

Imo State, created in 1976 in the South-East, appears better off on paper. Poverty rates, at around 30–35 percent, are lower than the national average. IGR ranges between ₦35–45 billion annually. Literacy rates are high. Diaspora remittances are significant. Entrepreneurship is deeply embedded in Igbo culture.

Yet the state underperforms dramatically relative to its human capital. Imo has no coherent industrial policy. Manufacturing is weak. Innovation hubs are absent. Businesses relocate to Lagos, Anambra, or outside Nigeria altogether. Insecurity — fueled by poor governance and state incapacity — has further crippled investment.

The paradox is stark: a highly educated population trapped in an economy with limited productive outlets. Talent leaves. Capital follows. The state consumes what others produce.

Imo’s failure is not intellectual; it is administrative. Human capital without structure becomes export labor.

NIGER STATE: POWER WITHOUT PROSPERITY

Niger State is Nigeria’s largest by land mass and one of its most resource-endowed. Created in 1976, it hosts major hydroelectric dams — Kainji, Shiroro, and Jebba — which generate electricity for the nation. Yet Niger State itself remains energy-poor.

Poverty exceeds 60 percent. IGR struggles to reach ₦20 billion. Industrial activity is minimal. Urban centers are weak. Rural poverty is widespread.

This is one of Nigeria’s most glaring development contradictions: a state that produces power but does not use it to industrialize. No energy-driven manufacturing clusters. No downstream industries. No integrated development around its dams. Power exists, but prosperity does not.

The failure here is strategic. Infrastructure without industrial policy is symbolic, not transformative.

OGUN STATE: ESCAPING DEPENDENCY — BY ACCIDENT

Among the states created in 1976, Ogun stands out as the relative success story. Located in the South-West, it records poverty rates of 20–25 percent and generates between ₦80–100 billion annually in IGR. It hosts industrial parks, factories, logistics hubs, and multinational manufacturers.

But Ogun’s success requires honesty. Its growth is largely a spillover from Lagos — Nigeria’s economic engine. Proximity, not superior governance, explains much of Ogun’s industrial attraction. Companies priced out of Lagos simply crossed the border.

Even so, Ogun underperforms its potential. Roads are poor. Infrastructure lags behind industrial growth. Urban planning is weak. With intentional governance, Ogun should be growing exponentially like Lagos. Instead, it grows incrementally.

Ogun escaped dependency, yes — but not through visionary leadership. It benefited from geography more than policy.

Read also:

- Company restates commitment to deliver one million affordable homes

- NIWA inaugurates search, rescue centre in Lagos

- Sugar daddy, 54, pours acid on girlfriend, 18

ONDO STATE: RESOURCE-RICH, CASH-POOR

Ondo State, created in 1976, is oil-producing yet poorly diversified. Poverty rates range between 30–35 percent. IGR stands at about ₦30–40 billion annually. Oil revenues came, but long-term assets did not.

There was no strategic reinvestment into manufacturing, maritime economy, or agro-industrialization. The coastal advantage remains underdeveloped. The private sector is weak. Youth migration is high.

Ondo exemplifies Nigeria’s resource curse at the subnational level: extractive income without structural transformation. Fifty years later, the oil is largely gone — and so is the opportunity.

OYO STATE: THE PAINFUL DECLINE OF A GIANT

Oyo State’s story hurts the most. Created in 1976 with Ibadan as its capital, Oyo inherited extraordinary advantages. Ibadan was once the largest city in West Africa. It hosted Nigeria’s first university, the intellectual heart of the old Western Region, and a hub of publishing, research, commerce, and industry. This was a state that started ahead.

Today, poverty stands at 28–32 percent. IGR, at ₦45–60 billion, is modest for its size and history. Youth unemployment is high. Most factories are gone. Industrial estates are abandoned. Ibadan now exports graduates, not products.

Lagos absorbed the economic energy Oyo failed to retain. What should have been Nigeria’s second economic pole became a feeder city.

Oyo is not poor because it lacked history. It is poor because it failed to convert history into modern productivity.

THE BIGGER TRUTH: STATE CREATION DID NOT CREATE DEVELOPMENT

Out of the states created 50 years ago, only Ogun clearly escaped total dependency — and even that escape was accidental. The rest still survive on Abuja allocations. This is not coincidence. It is structure.

Nigeria mistook administrative multiplication for economic strategy. State creation created governors, assemblies, and bureaucracies — not industries, markets, or productivity.

Poverty in these states is structural, not accidental. It is the result of: Visionless leadership; Absence of long-term planning; Overdependence on federal transfers; Failure to industrialize Lack of accountability.

If Nigeria does not admit this truth, the next 50 years will be another anniversary without progress. Development is not a slogan. It is a system. And systems are built by leaders who choose productivity over power.